More than a year and a half after the City of Denver first tried to crack down on short-term rentals, the nascent industry — buoyed by thousands of hosts — has consistently stayed one step ahead of its regulators.

A review of city records, combined with data provided by Denver-based analytics firm AirDNA, exposes systematic problems across the city’s efforts to control a market that now brings in more than $100 million a year.

The result: To date, less than half of the city’s known short-term rental landlords comply with existing regulations, which require hosts be licensed by the city and be the primary resident of the home they’re renting.

The primary-residence requirement, designed to calm the fears of homeowners concerned that their residential neighborhoods could become dominated by “the motel next door,” has proven toothless and largely unenforceable.

The State of the Short-Term Market

According to data from the Denver Department of Excise and Licenses, the regulatory agency charged with enforcing compliance across the city’s more than 180 different business licenses, 2,200 of 4,300 short-term rentals are illegal because they lack a license. That’s a compliance rate of 49 percent. And nearly identical to last summer, when BusinessDen reported a 50 percent compliance rate with 2,000 fewer units in Denver.

“We believe the compliance rate is going down because we are seeing a surge in people listing short-term rentals in Denver,” said Eric Escudero, communication’s director for Excise and Licenses.

At the same time, the short-term rental industry in the Denver region has swollen to be worth at least $112 million in the last 12 months, according to an analysis of AirDNA data. The analytics firm defines the region as the city itself and select outlying communities, but the city accounts for the majority of listings.

That $112 million figure is up 170 percent from the same period two years ago, when the industry pulled in $41 million between August 2016 and July 2017.

The most recent market estimate represents about 6.5 percent of the $1.7 billion that Denver hotels made last year, according to travel research firm Longwoods International.

The short-term rental market’s growth has been almost linear since 2016. And at its current growth rate, it will top $200 million in 2021.

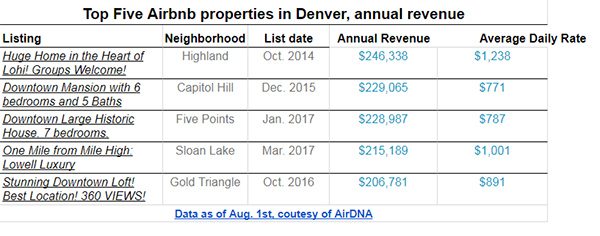

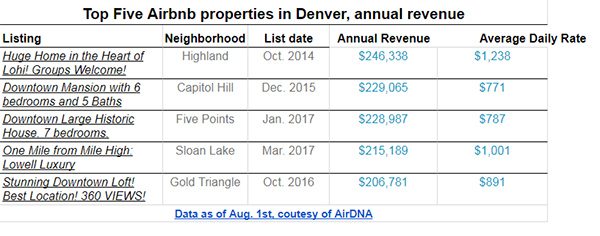

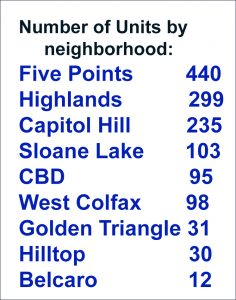

That’s a tempting pot of gold for landlords who can make far more with a short-term rental than a traditional tenant on a year lease. And for dozens of properties in prime locations, like The Highlands, annual cash flow can top six figures, according to AirDNA.

In theory, the city’s regulations concerning primary residences should prevent property owners from running more than one Airbnb location, and from renting a house every day of the year unless it is a secondary unit like a mother-in-law basement or carriage house at their home. (They need a place to live, after all.)

But according to AirDNA, at least 39 percent of the city’s Airbnb properties are offered to guests full time, year-round. Most listings reviewed by BusinessDen were entire homes, not auxiliary dwelling units.

According to AirDNA, at least 17 percent of Airbnb hosts run more than one property, which would appear to be prohibited altogether under Denver law, given the primary-residence clause. Those multilisting hosts account for 40 percent of the city’s rentals on Airbnb — a total of nearly 2,000 listings.

If you ask the Department of Excise and Licenses, the poor compliance is not for lack of trying.

“Our overall regulatory goal has been to balance the needs and wants of everyone in Denver,” said Ashley Kilroy, director of Excise and Licenses. “We need to give people the opportunity to rent out their homes as short-term rentals but balance the needs and wants of residential neighborhoods.”

When it comes to regulating short-term rentals, officials are generally optimistic: They say Denver’s compliance rate is comparable to sister cities such as San Francisco, the birthplace of Airbnb. The city’s licensing process for short-term rentals is automated and online, which streamlines the process for potential hosts. The city even received a commendation from the U.S. Conference of Mayors in 2017 for its approach to regulating short-term rentals.

But staring down the barrel of 2,200 unlicensed rentals and nearly 2,000 listings run by multi-unit hosts, Excise and Licenses has one man: Brian Snow, short-term rental compliance officer. Six inspectors also help get the city’s short-term renters in check. But those six inspectors are also responsible for monitoring compliance for the city’s 180 other business licenses.

“They’re undermanned and understaffed,” said George Mayl, president of Inter-Neighborhood Cooperation and a member of the city’s Short-term Rental Advisory Committee. “The folks inside Excise and Licenses work really, really hard, but at the end of the day they need more people.”

At any given time, the inspectors inside Excise and Licenses are juggling between 50 and 70 investigations into unlicensed and out-of-compliance short-term rental properties.

Most of the license-related notices of violation (NOVs) are sent by Host Compliance, a vendor the city hired in 2016 to scour short-term rental websites and find unlicensed properties. After finding a listing and determining its address, the city said its own personnel often will spend additional time verifying they have the right place and that an actual short-term rental is being operated “to avoid wasting time,” according to Kilroy.

Since mid-May, the city said it has sent out at least 121 notices of violation involving short-term listings that advertise without a license. Approximately 85 percent of the property owners notified either removed their listings or applied for one.

Beyond getting hosts into the system, however, making sure they’re actually following the rules is a different challenge. For now, the city’s enforcement system for primary residences is driven by a single force: neighborly complaints.

Between January and July, the city received 112 complaints through 311 concerning primary residence, typically from neighbors. Of those, Excise and Licenses said they had completed 53 reports, of which 47 property owners were able to prove they were the primary resident of the home they were renting.

With the six remaining properties, the City Attorney’s Office was brought in to determine actual primary residence. That figure is dwarfed by the roughly 2,000 listings that AirDNA said are run by multi-unit hosts.

Some residents, such as Mayl, argue that it’s unfair to expect neighbors to be the driving force behind legal compliance.

“If part of the taxes the city received for short-term rentals went back into the compliance enforcement, enforcement would pay for itself,” Mayl said. “That’s not what’s happening.”

The city announced last month that it had received $3 million in lodging taxes from short-term rentals between January and July, a victory made possible in part by an agreement Denver reached with Airbnb in April for the company to collect taxes on the city’s behalf, rather than forcing hosts to send the taxes to Denver on their own initiative.

For the city’s part, its application process for short-term licenses wasn’t conducive to actually enforcing the primary-residence rule until last week, when the city for the first time began requiring applicants to upload documents such as utility bills or tax forms showing an address matching the applicant’s driver’s license.

Prior to that, the city requested similar documentation only upon receiving a complaint.

“Our compliance figures have not been affected yet,” communications director Escudero said. “But we anticipate this will improve compliance for primary-residence requirements.”

Since Airbnb arrived in Colorado 10 years ago, Denver has had a cumulative total of more than 15,000 listings across the metro area, according to AirDNA. Kilroy, director of Excise and Licenses, said that wrangling the industry will be no small task as it continues to expand.

“The problem is, the industry is evolving as quickly as we are,” Kilroy said. “We’re finding that with so much of what we do — marijuana, short-term rentals, scooters — we’re always facing those evolving industries.”

More than a year and a half after the City of Denver first tried to crack down on short-term rentals, the nascent industry — buoyed by thousands of hosts — has consistently stayed one step ahead of its regulators.

A review of city records, combined with data provided by Denver-based analytics firm AirDNA, exposes systematic problems across the city’s efforts to control a market that now brings in more than $100 million a year.

The result: To date, less than half of the city’s known short-term rental landlords comply with existing regulations, which require hosts be licensed by the city and be the primary resident of the home they’re renting.

The primary-residence requirement, designed to calm the fears of homeowners concerned that their residential neighborhoods could become dominated by “the motel next door,” has proven toothless and largely unenforceable.

The State of the Short-Term Market

According to data from the Denver Department of Excise and Licenses, the regulatory agency charged with enforcing compliance across the city’s more than 180 different business licenses, 2,200 of 4,300 short-term rentals are illegal because they lack a license. That’s a compliance rate of 49 percent. And nearly identical to last summer, when BusinessDen reported a 50 percent compliance rate with 2,000 fewer units in Denver.

“We believe the compliance rate is going down because we are seeing a surge in people listing short-term rentals in Denver,” said Eric Escudero, communication’s director for Excise and Licenses.

At the same time, the short-term rental industry in the Denver region has swollen to be worth at least $112 million in the last 12 months, according to an analysis of AirDNA data. The analytics firm defines the region as the city itself and select outlying communities, but the city accounts for the majority of listings.

That $112 million figure is up 170 percent from the same period two years ago, when the industry pulled in $41 million between August 2016 and July 2017.

The most recent market estimate represents about 6.5 percent of the $1.7 billion that Denver hotels made last year, according to travel research firm Longwoods International.

The short-term rental market’s growth has been almost linear since 2016. And at its current growth rate, it will top $200 million in 2021.

That’s a tempting pot of gold for landlords who can make far more with a short-term rental than a traditional tenant on a year lease. And for dozens of properties in prime locations, like The Highlands, annual cash flow can top six figures, according to AirDNA.

In theory, the city’s regulations concerning primary residences should prevent property owners from running more than one Airbnb location, and from renting a house every day of the year unless it is a secondary unit like a mother-in-law basement or carriage house at their home. (They need a place to live, after all.)

But according to AirDNA, at least 39 percent of the city’s Airbnb properties are offered to guests full time, year-round. Most listings reviewed by BusinessDen were entire homes, not auxiliary dwelling units.

According to AirDNA, at least 17 percent of Airbnb hosts run more than one property, which would appear to be prohibited altogether under Denver law, given the primary-residence clause. Those multilisting hosts account for 40 percent of the city’s rentals on Airbnb — a total of nearly 2,000 listings.

If you ask the Department of Excise and Licenses, the poor compliance is not for lack of trying.

“Our overall regulatory goal has been to balance the needs and wants of everyone in Denver,” said Ashley Kilroy, director of Excise and Licenses. “We need to give people the opportunity to rent out their homes as short-term rentals but balance the needs and wants of residential neighborhoods.”

When it comes to regulating short-term rentals, officials are generally optimistic: They say Denver’s compliance rate is comparable to sister cities such as San Francisco, the birthplace of Airbnb. The city’s licensing process for short-term rentals is automated and online, which streamlines the process for potential hosts. The city even received a commendation from the U.S. Conference of Mayors in 2017 for its approach to regulating short-term rentals.

But staring down the barrel of 2,200 unlicensed rentals and nearly 2,000 listings run by multi-unit hosts, Excise and Licenses has one man: Brian Snow, short-term rental compliance officer. Six inspectors also help get the city’s short-term renters in check. But those six inspectors are also responsible for monitoring compliance for the city’s 180 other business licenses.

“They’re undermanned and understaffed,” said George Mayl, president of Inter-Neighborhood Cooperation and a member of the city’s Short-term Rental Advisory Committee. “The folks inside Excise and Licenses work really, really hard, but at the end of the day they need more people.”

At any given time, the inspectors inside Excise and Licenses are juggling between 50 and 70 investigations into unlicensed and out-of-compliance short-term rental properties.

Most of the license-related notices of violation (NOVs) are sent by Host Compliance, a vendor the city hired in 2016 to scour short-term rental websites and find unlicensed properties. After finding a listing and determining its address, the city said its own personnel often will spend additional time verifying they have the right place and that an actual short-term rental is being operated “to avoid wasting time,” according to Kilroy.

Since mid-May, the city said it has sent out at least 121 notices of violation involving short-term listings that advertise without a license. Approximately 85 percent of the property owners notified either removed their listings or applied for one.

Beyond getting hosts into the system, however, making sure they’re actually following the rules is a different challenge. For now, the city’s enforcement system for primary residences is driven by a single force: neighborly complaints.

Between January and July, the city received 112 complaints through 311 concerning primary residence, typically from neighbors. Of those, Excise and Licenses said they had completed 53 reports, of which 47 property owners were able to prove they were the primary resident of the home they were renting.

With the six remaining properties, the City Attorney’s Office was brought in to determine actual primary residence. That figure is dwarfed by the roughly 2,000 listings that AirDNA said are run by multi-unit hosts.

Some residents, such as Mayl, argue that it’s unfair to expect neighbors to be the driving force behind legal compliance.

“If part of the taxes the city received for short-term rentals went back into the compliance enforcement, enforcement would pay for itself,” Mayl said. “That’s not what’s happening.”

The city announced last month that it had received $3 million in lodging taxes from short-term rentals between January and July, a victory made possible in part by an agreement Denver reached with Airbnb in April for the company to collect taxes on the city’s behalf, rather than forcing hosts to send the taxes to Denver on their own initiative.

For the city’s part, its application process for short-term licenses wasn’t conducive to actually enforcing the primary-residence rule until last week, when the city for the first time began requiring applicants to upload documents such as utility bills or tax forms showing an address matching the applicant’s driver’s license.

Prior to that, the city requested similar documentation only upon receiving a complaint.

“Our compliance figures have not been affected yet,” communications director Escudero said. “But we anticipate this will improve compliance for primary-residence requirements.”

Since Airbnb arrived in Colorado 10 years ago, Denver has had a cumulative total of more than 15,000 listings across the metro area, according to AirDNA. Kilroy, director of Excise and Licenses, said that wrangling the industry will be no small task as it continues to expand.

“The problem is, the industry is evolving as quickly as we are,” Kilroy said. “We’re finding that with so much of what we do — marijuana, short-term rentals, scooters — we’re always facing those evolving industries.”

Good. There shouldn’t be any regulations or rules in the first place.

I agree with Kevin. Let the free market reign. The city of Denver, with its corrupt mayor and totally dishonest city council, has no business telling private property owners what to do…clean-up your own house before telling us how to handle ours. Councilwoman Mary Beth S has lied to her

constituents without a moment’s hesitation. Ask the people in the Crestmoor neighborhood about her hidden emails and the sneaky way she manipulated a zoning change.

Screw the city of Denver.

A few days ago I read about the “art” – the lighted broken snow fence you see on the way to the airport – it cost the city $14 million dollars and, thus far, they’ve paid off $21,000 of the bill. Today, I heard Mayor, Where’s my prostitute? Hancock whining on the radio about affordable housing funds

and the need for more money. He said they need around $15 million. Well DUH. The city can’t handle its finances but they want their greedy little hands on the money earned by landlords. And lately we’ve been hearing about Denver citizens being responsible for replacing their own sidewalks – even though the city owns the property.

It’s time that we stop tolerating government bullshit.