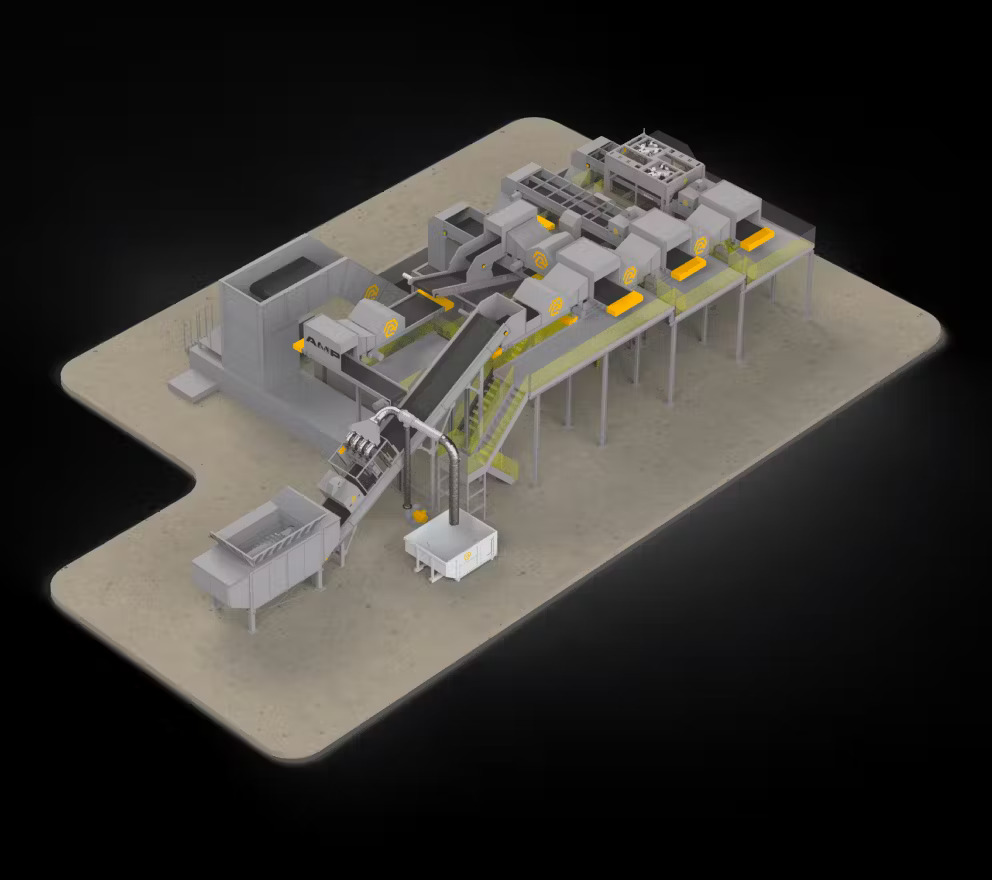

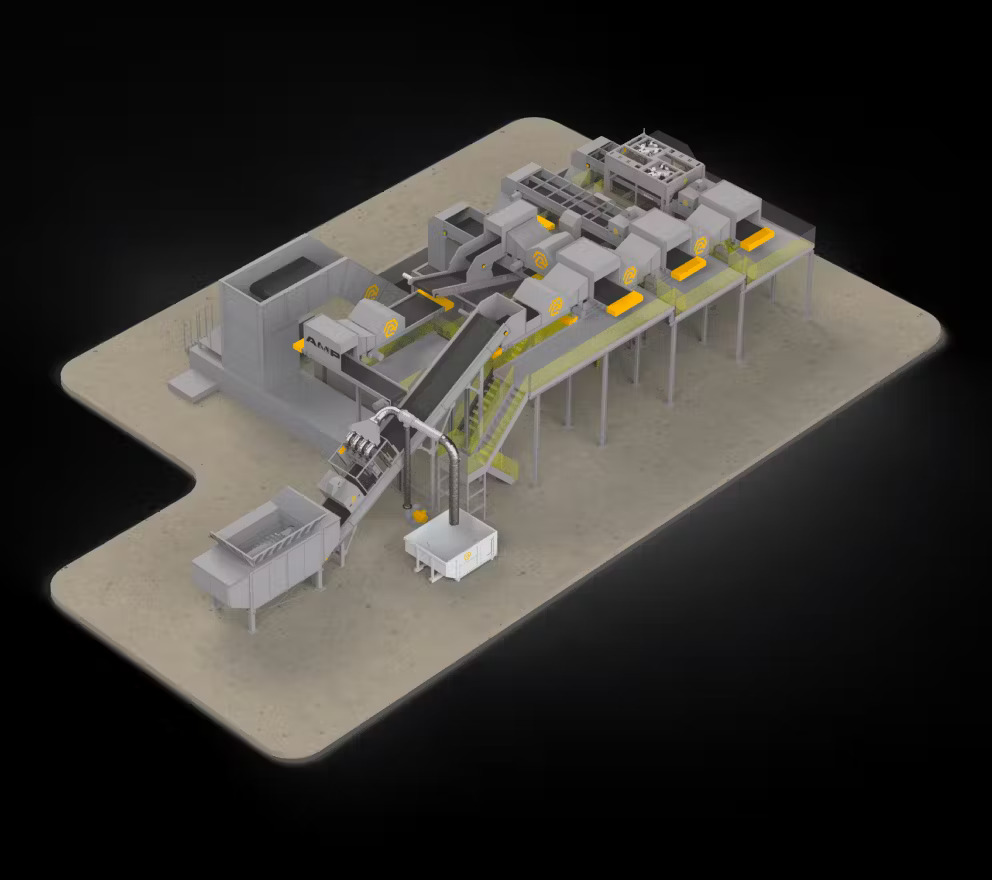

The AMP ONE system separates plastics, metals and the like using machine learning. (Courtesy AMP)

Only 21 percent of waste across the country actually gets recycled, according to nonprofit The Recycling Partnership. That number drops again when zooming in on the Centennial State, which reported a 15.5 percent rate last year.

But in 2026, a recycling facility aiming to quadruple that number will open in Commerce City.

“These capabilities haven’t been possible until now,” said Mantanya Horowitz, founder of Louisville-based AMP. “It’s a big step up in terms of what we can do.”

His business has been sorting trash using AI technology for a decade, aiming to improve rates through its AMP ONE system, which separates plastics, metals and the like using machine learning. Instead of glass getting lumped in with garbage meant for a landfill, AMP’s robots will set it to the side, helping it reach over a 60 percent recycling rate.

Mantanya Horowitz

“It’s essentially a garbage sensor,” Horowitz said, explaining how AMP teaches its systems to recognize any type of waste. “With that, you can build all sorts of machines.”

Now, AMP is working with Waste Connections, the publicly traded trash collector, to build its system in the latter’s 72,000-square-foot space at 4150 E 60th Ave. Horowitz said AMP expects to sort and sell over 62,000 tons of what people annually throw in recycling bins around the Denver metro area.

AMP currently has three similar systems operating across the country — one each in Ohio, North Carolina and Virginia — which have been in use for a couple of years. AMP charges its customers on a ton-per-month basis, Horowitz said. Along with the tech, it takes one to one dozen people to run a plant, he said.

“It’s all about cost savings for the waste companies,” Horowitz explained, citing the high transport and sorting costs for recycled materials. “The recycling industry is a cost for waste companies and municipalities, and even when it’s working, it’s not a lucrative business. Right now, it’s just this peripheral add- on.”

Along with those costs, recycling rates are so low because most waste companies are contracted with single-family homes and apartment buildings, leaving out large swaths of trash that come from entities such as stadiums, he said. By making recycling more efficient and profitable, Horowitz hopes to incentivize the Waste Connections of the world to implement AMP’s tech.

“We go to waste companies and say, ‘We’re going to help sort it out and sell it,’” he said. “The real goal here is to go after a massive opportunity, to make a little margin on every pound of garbage in the world.”

AMP also recently announced a $91 million Series D raise to continue to build out its facilities. The round was backed by Sequoia Capital, Liberty Mutual Investments and Range Ventures, the Denver-based group that put in around $1 million. This round brings AMP’s total investment to over $270 million.

In November, the business tapped Tim Stuart, former chief operating officer of waste company Republic Services, as CEO. Horowitz, who manned that role before, stepped down to the role of chief technology officer.

Horowitz founded AMP while in grad school studying robotics and artificial intelligence. From 2013 to 2014, he looked to transpose autonomous car technology to another industry and settled on recycling without any prior connections to the industry.

“There’s real value from what’s in your garbage,” he said. “And AI allows you to pull commodities and get that value.”

AMP received nearly $500,000 in grant funding during its first several years, something Horowitz believes helped his company attract hundreds of millions in venture capital to date. Because the waste and recycling industry depends on municipal contracts and stingy hardware, among other things, that makes startups in that space difficult to invest in.

“But those grants enabled us to bring down costs and show there’s a customer base,” he said. “That de-risking was necessary to raise VC.”

A robotic sorting arm created by Louisville-based AMP. (Courtesy AMP)

At the time, AMP was adding its AI-powered robotic arms to pre-existing waste facilities, deploying 400 around the world to date. But about five years ago, the focus switched to building out their own operations.

“There was only so far you could get retrofitting those,” Horowitz said. “With recycling rates going down, the big question is how you reverse that trend on the whole. That wasn’t going to happen with just our arms.”

Earlier this year, AMP institutionalized that change, dropping “robotics” from the second half of its name, which the company was known by since its founding in 2014. Its focus is now on building its recycling facilities, much like the one in Commerce City.

“There are hundreds of recycling facilities,” said AMP spokeswoman Carling Spelhaug. “And with recycling rates being less than half of what they should be, we see opportunities for hundreds of facilities.”

The AMP ONE system separates plastics, metals and the like using machine learning. (Courtesy AMP)

Only 21 percent of waste across the country actually gets recycled, according to nonprofit The Recycling Partnership. That number drops again when zooming in on the Centennial State, which reported a 15.5 percent rate last year.

But in 2026, a recycling facility aiming to quadruple that number will open in Commerce City.

“These capabilities haven’t been possible until now,” said Mantanya Horowitz, founder of Louisville-based AMP. “It’s a big step up in terms of what we can do.”

His business has been sorting trash using AI technology for a decade, aiming to improve rates through its AMP ONE system, which separates plastics, metals and the like using machine learning. Instead of glass getting lumped in with garbage meant for a landfill, AMP’s robots will set it to the side, helping it reach over a 60 percent recycling rate.

Mantanya Horowitz

“It’s essentially a garbage sensor,” Horowitz said, explaining how AMP teaches its systems to recognize any type of waste. “With that, you can build all sorts of machines.”

Now, AMP is working with Waste Connections, the publicly traded trash collector, to build its system in the latter’s 72,000-square-foot space at 4150 E 60th Ave. Horowitz said AMP expects to sort and sell over 62,000 tons of what people annually throw in recycling bins around the Denver metro area.

AMP currently has three similar systems operating across the country — one each in Ohio, North Carolina and Virginia — which have been in use for a couple of years. AMP charges its customers on a ton-per-month basis, Horowitz said. Along with the tech, it takes one to one dozen people to run a plant, he said.

“It’s all about cost savings for the waste companies,” Horowitz explained, citing the high transport and sorting costs for recycled materials. “The recycling industry is a cost for waste companies and municipalities, and even when it’s working, it’s not a lucrative business. Right now, it’s just this peripheral add- on.”

Along with those costs, recycling rates are so low because most waste companies are contracted with single-family homes and apartment buildings, leaving out large swaths of trash that come from entities such as stadiums, he said. By making recycling more efficient and profitable, Horowitz hopes to incentivize the Waste Connections of the world to implement AMP’s tech.

“We go to waste companies and say, ‘We’re going to help sort it out and sell it,’” he said. “The real goal here is to go after a massive opportunity, to make a little margin on every pound of garbage in the world.”

AMP also recently announced a $91 million Series D raise to continue to build out its facilities. The round was backed by Sequoia Capital, Liberty Mutual Investments and Range Ventures, the Denver-based group that put in around $1 million. This round brings AMP’s total investment to over $270 million.

In November, the business tapped Tim Stuart, former chief operating officer of waste company Republic Services, as CEO. Horowitz, who manned that role before, stepped down to the role of chief technology officer.

Horowitz founded AMP while in grad school studying robotics and artificial intelligence. From 2013 to 2014, he looked to transpose autonomous car technology to another industry and settled on recycling without any prior connections to the industry.

“There’s real value from what’s in your garbage,” he said. “And AI allows you to pull commodities and get that value.”

AMP received nearly $500,000 in grant funding during its first several years, something Horowitz believes helped his company attract hundreds of millions in venture capital to date. Because the waste and recycling industry depends on municipal contracts and stingy hardware, among other things, that makes startups in that space difficult to invest in.

“But those grants enabled us to bring down costs and show there’s a customer base,” he said. “That de-risking was necessary to raise VC.”

A robotic sorting arm created by Louisville-based AMP. (Courtesy AMP)

At the time, AMP was adding its AI-powered robotic arms to pre-existing waste facilities, deploying 400 around the world to date. But about five years ago, the focus switched to building out their own operations.

“There was only so far you could get retrofitting those,” Horowitz said. “With recycling rates going down, the big question is how you reverse that trend on the whole. That wasn’t going to happen with just our arms.”

Earlier this year, AMP institutionalized that change, dropping “robotics” from the second half of its name, which the company was known by since its founding in 2014. Its focus is now on building its recycling facilities, much like the one in Commerce City.

“There are hundreds of recycling facilities,” said AMP spokeswoman Carling Spelhaug. “And with recycling rates being less than half of what they should be, we see opportunities for hundreds of facilities.”